Speech to Islam Awareness Week Launch, 26 August 2013 at Whare Waka, Wellington

Shalom aleikhem, Salaam aleikum, Kia ora tatau.

On the tenth anniversary of Islam Awareness Week, we can say that we have spent significant time together. Not only are we more aware of each other, we are friends that know, like, trust, and respect each other. This is the perfect time to roll up are sleeves and start doing some hard work together.

Judaism and Islam are like brothers, as embodied in the relationship between Isaac and Ishmael. Our common father Abraham is a towering figure in our sacred texts, and his teachings and ethical guidance are central to both our religions.

Isaac and Ishmael never knew each other properly as brothers, as according to the Torah, Ishmael and his mother Hagar were banished shortly after Isaac was weaned (Genesis 21:14); they did not see each other again until Abraham was buried (Genesis 25:9).

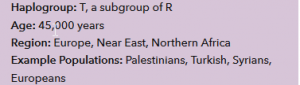

Not only are we brothers in the spiritual sense, we are actually brothers in the biological sense. I recently subscribed to a service called 23andme, where you spit into a small vial, send it off to the lab, they sequence your genome and tell you all sorts of interesting things about yourself. In my case, they correctly predicted that I have type O+ blood (which has a significantly lower prevalence in Ashkenazim than in the general population), and blue eyes. They also said that I am likely to have straight hair, so they’re not perfect. They say I’m 93.9% Ashekenazi Jewish. But if you look more closely at my maternal haplotype, T, the top listed example population is: Palestinans.

Through the millennia and centuries our ancestors have lived as brothers; much of the time the relationship has been good, but at other times, and particularly modern times, there has been lots of room for improvement.

The story of our difficult times owes more to politics than to our religious differences – but there is a definite religious angle to these political issues which is ignored or denied at our own peril.

Right now, today, these differences centre on events in Israel and Palestine. At its core, the central problem is that both Jews and Palestinians believe that the land is theirs. In Māori terms, both iwi believe that they have tangatawhenuatanga over the holy land. Problem is, both are right. When my Māori friends start talking about the Jews as colonisers and Palestinians as colonised, it’s time for a history lesson, as things are not quite so simple.

Here’s a concrete example from my own family. My niece grew up in Los Angeles and “made aliyah” (ie immigrated) to Israel about ten years ago, and married a lovely young man, a statistician from the Gilo neighbourhood in Jerusalem. I attended the wedding will never forget her soon-to-be Father-in-law Yossi asking me about New Zealand. “Who does it border?” he asked. “It’s a series of islands surrounded by thousands of kilometres of water,” I answered, “the nearest neighbour is Australia, 3-1/2 hours away by plane”. “Is there much water there?” “It generally rains every week. Where I live, we get about 1300mm of rain every year. It’s very green”. He paused, and looked at me and said, “it sounds like Paradise”.

Gilo sits in that part of the West Bank that was annexed by the Israeli government after it was recaptured in the 1967 war, and is now part of the Jerusalem Municipality. The land on which Gilo was built was legally purchased by Jews before the second world war, before the land was captured by the Egyptian army in the 1948 war and became part of Jordan. In biblical times Gilo was an important town. The land was largely vacant until modern Gilo was built in 1971.

My point is that it’s very messy. Occupied territory, or Jerusalem neighbourhood? There is some truth to both statements, and the contradictory truths seem blindingly obvious to people on both sides. And it is exactly these perplexing problems involving the lives of real people and contradictory narratives which we must navigate in order to make progress.

I will tell you this though – a sustainable peace will not be black and white, involving the complete victory of one side over the other. Neither side is about to quit the land, and we had better do what we can to encourage the feuding brothers to reconcile lest the situation result in mutual annihilation.

Here, in Yossi’s Paradise, we have an opportunity to overcome our differences far away from the source of the problems. Perhaps we can exhibit more generous and mature brotherly behaviour when we’re removed from the fighting and conflict over resources.

I have close personal experience of reconciling brothers. I am the father of three sons, currently age 21, 17 and 10. When they were younger, the eldest and middle boys used to squabble and fight continually. When the eldest went away to university, they both realised what they had been missing. Ever since, they’ve been best mates and whenever the eldest is in town they spend a lot of time together.

We can make progress by exploring the relationship with our brothers with an open heart. But we must look at things warts and all, and not seek a kumbaya moment by ignoring the bad stuff from the past. It won’t last, and we need to build a sustainable future.

Part of this process of reconciliation relies on good faith, and liberal application of the Golden Rule. In the Talmud, this is stated as “what is hateful to you, do not to to another person”, and derives directly from the biblical commandment to “love your neighbour as yourself”.

This rule also appears in many places in the Hadith, for example Sahih Muslim, Book 1, 72:

Anas ibn Malik (may Allah be pleased with him) reported: The Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, said: “None of you has faith until he loves for his brother or his neighbor what he loves for himself.”

These same principles form the foundation of Karen Armstrong’s Charter for Compassion, an excellent blueprint for how we can get along with each other.

This week, in the leadup to our Days of Awe and the Jewish New Year (similar in many ways to Ramadan) we are reading the Torah portion Nitzavim, in which Moses (pbuh) is delivering his final lecture to the Jewish people. He tells us that we have the choice between a blessing and a curse; the blessing should we act according to God’s will, and the curse if we do not.

It is not in heaven, that you should say, “Who will go up to heaven for us and fetch it for us, to tell [it] to us, so that we can fulfill it?: Nor is it beyond the sea, that you should say, “Who will cross to the other side of the sea for us and fetch it for us, to tell [it] to us, so that we can fulfill it?” Rather, [this] thing is very close to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you can fulfill it. [Deuteronomy 30:12-14]

Ultimately we are commanded to “choose life”.

It is in our capacity to learn about each other and treat each other with the compassion that is in both of our religious traditions, and work to respect even the things within each other that we do not like. For that is at the heart of love – the ability to empathise, and to work together even though you may not like everything about each other. We’ll never like everything about each other, but we shouldn’t let that get in the way of working together for a better New Zealand, and a better world.

To make this happen at a personal and organisational level, speaking as the Jewish Co-Chair of the Wellington Council of Christians and Jews, in the next year it is our stated intention to extend our hands to our Muslim brothers and sisters, and transform that organisation into an Abrahamic Council. In that way we will be able to continue our dialogue, or rather trialogue as mature equals.

So let us get to know each other, and transform our childhood squabbles into mature, adult brotherly love. We can only do that with a complete, unreserved understanding of each other and our historical narratives.

Thank you.