Content warning: This article describes a family’s experience with Medical Aid in Dying (MAID), including detailed discussion of dementia, end-of-life planning, and death.

My mother, Dr Sarah Traister Moskovitz, died on 1 September 2024 through Medical Aid in Dying (MAID). It was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever witnessed. She was 97 years old.

Mom’s memory started deteriorating in her mid 80’s, with general forgetfulness, and an increasing inability to manage her own calendar. As she approached her 90’s, her ability to drive a car became sufficiently bad that we, her children, had to convince her rather emphatically to stop driving. Her eye-hand coordination deteriorated to the extent that she was unable to use a cellphone. Her memory became noticeably worse. She’d forget that she had food cooking on the stove, and would occasionally burn out the pan. This trend accelerated during the COVID pandemic. In 2020, at age 92, it got bad enough that she sought medical advice. Her GP recommended that she see a specialist, even though she was in a state of disbelief about a possible diagnosis of early stage Alzheimers.

She enrolled with a healthcare provider that gave her a neurologist, a neuropsychologist, and a psychiatrist. At her initial interview, the neuropsychologist gave her a battery of memory tests, which showed that her brain was functioning at near-normal levels for someone in their 90s. This was followed up by regular MoCA (“Montreal Cognitive Assessment”) short memory test assessments. These MoCA tests ask questions like what day is it today? What city do you live in? Can you draw a clock face showing the time at 11:15? Please draw a copy of this simple picture, please repeat this list of five words to me, etc.

She was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). She had been a professor of educational psychology during her career, and was used to operating at the top of her mental game. She felt inept at things she used to excel at. She hated the loss of agency, having other people do things for her that she was used to doing for herself. She could feel herself slowly losing control over herself. She was terrified of, in her words, “turning into a vegetable and being filed away in a board-and-care”.

She was terrified of, in her words, “turning into a vegetable and being filed away in a board-and-care.”

Her neurologist prescribed Aricept and Exelon to arrest the development of the dementia. It’s difficult to determine whether these drugs had any real effect.

In addition to these medical physicians, Mom was offered sessions with Ryan Glatt, a cognitive physiotherapist who runs a “brain gym” in Santa Monica. I went to Mom’s weekly sessions with Ryan regularly, in person when I was in town, and online when I wasn’t. The idea behind cognitive physiotherapy is that you can arrest the progress of dementia by simultaneously increasing blood flow to the brain through exercise, while performing complex cognitive tasks. During these sessions, Mom would play a variety of video games, including identifying matching letters on a big screen while marching, and a complicated version of Dance Dance. But the most interesting activity was a game where Mom was on a stationary bike, pedalling hard, wearing a VR headset, and chasing a cartoon dog through a forest while catching coloured gems – red gems in the right hand and blue gems in the left. I never thought I’d live to see the day when Mom would wear a VR headset, especially at age 90-something – she was right up there with the cool kids, and looked like a space alien. But life is full of surprises.

Mom’s MoCA test scores were relatively stable, showing a very slow decline over time. her hearing seemed to deteriorate in parallel with her mental acuity. I saw a connection between the two. Deafness results in the inability to follow conversations, misunderstanding, and ultimately social isolation. All of these factors are unhelpful to dementia.

Mom and Dad lived in the same house I grew up in, for over 56 years. They were inseparable.

Dad was six weeks older than Mom, had a number of significant medical issues, and was debilitated by severe lower back pain. It got to the point that having lived independently for so long, both Mom and Dad now needed home help. They started with eight hours per day six days a week, which was ramped up to 24/7 in mid 2022, when Dad became mostly housebound. He couldn’t really wake up in the day, and couldn’t really sleep at night.

Mom resolved that she would not end her life in one of these units. And Dad did not want to leave the house that he’d lived in for so long, with his workbench, even though he rarely felt well enough to use it. So we went with the 24×7 home care option. Mom and Dad had the foresight in their earlier years to get long-term care insurance, which covered a significant portion of the costs.

About this time, we started investigating aged care facilities that might be socially better and possibly less expensive than 24/7 care. There was an issue though – if you have a dementia diagnosis, you can’t go into a rest home that does not have a memory care unit. As we toured these facilities, we asked to see their memory care units as well, knowing that Mom might very well end up there. Although some people were playing card games, and doing puzzles, others were staring into space, unable to control their movements, agitated. Mom was really frightened by this.

Mom also had a friend who had entered just such a memory care unit. Mom visited her a couple of times, but this friend did not recognise her, or anyone else, and couldn’t speak.

They both filled out POLST forms, telling any medical personnel “Do Not Resuscitate” in the event of a medical emergency. These forms were posted on the door to their bedroom so that any paramedics would see them on their way in.

In California, there are three criteria for MAID. You must: (1) Have a terminal condition with less than six months left to live (2) Be able to take the drugs yourself and (3) Be of sound mind.

Mom’s friend Edie across the street had done some reading about “death with dignity”, and Mom wanted to know more. In California, there are three criteria for MAID. You must: (1) Have a terminal condition with less than six months left to live (2) Be able to take the drugs yourself and (3) Be of sound mind. There is a “catch-22” though: you can’t really qualify for assisted death with a major diagnosis of dementia, because by the time you only have less than six months to live, you are almost certainly no longer of sound mind.

Mom knew that she had a heart condition which was serious enough to claim less than six months to live, but she knew she had to get the timing right. She didn’t want to die soon – there were so many interesting things happening in the world, especially in her family! But she knew if she left it too long and was no longer “of sound mind”, she would end up filed away in a memory care unit. She became worried that this would creep up on her quickly, and wanted to be able to act in time.

Over the next year, Mom’s condition started to deteriorate more rapidly. She had become more forgetful, more irritable, and could only barely walk around the block. Her MoCA scores began to decrease.

Then Dad took a turn for the worse. In November 2022 at age 95, he went into hospital with pneumonia, and after a couple of days, decided he was ready to go and didn’t want any more treatment. He pulled the IV tubes out of his arms and demanded to be taken home. So he was put on home hospice, in his bedroom. He had a nurse who administered morphine and lorazepam to make him comfortable. I was at a conference in Auckland when I got the news, and caught the next flight to LA.

The whole family started gathering, preparing for Dad’s death. I sat with him much of the time in his bedroom, and spent the nights in a chair next to his bed. On his fourth night at home, he seemed near death. He was talking incoherently in between morphine injections. At 4am, he said to me in Yiddish, “I don’t know which world I’m in”.

The family continued to gather, and the front room at the house was becoming a bit of an ongoing party. With three children, nine grandchildren, 14 great grandchildren, and partners, it was growing into quite a crowd. The next day, my niece Melody* arrived. She had a keen interest in photography, which she shared with Dad. They got into a deep conversation. After a while, Dad said that there were some photos he wanted to show Melody. So he got out of bed for the first time since coming back home from the hospital, walked down the hall without his crutches to the computer room, and started showing Melody some photos on his computer. I watched, surprised, as Dad got quite animated in his descriptions of his photos. After about a half hour, he got tired, and wanted to go back to bed. But as he was on his way back to bed, he noticed a lot of noise, people playing guitars and cracking jokes, coming from the front room. “What’s going on out there?” he asked. “Well”, I said, “you’re on hospice Dad, and all of your family members have come to say goodbye to you”. “I suppose I should say hello to them,” he said.

So instead of going straight back into his bedroom, he turned left and went into the living room where the party was going in full swing. He sat down at the table, had some food for the first time in a week, and started telling stories, singing songs, and enjoying the company. He eventually went back into his room, but that night he told the nurse he didn’t want any more morphine or lorazepam, and we took him off hospice. Everyone went home a couple of days later, and dad lasted another 10 months.

Mom was worried about what would happen if she needed to “check out” before Dad. He really needed her, and she didn’t want to leave him on his own.

After people left, Mom got serious with me. “Look,” she said, “I know I’m going to be ready to ‘check out’ soon.”

I know I’m going to be ready to ‘check out’ soon.

“How soon?” I asked.

“I don’t know, I’m not ready yet, maybe six months from now, but I don’t want to wait until it’s too late.”

Where to turn? Mom’s primary health care provider was a Catholic company, and Mom’s GP Dr Goldstein* said she couldn’t go anywhere near this due to company policy. Luckily Mom’s rabbi, Rabbi Amy, came to the rescue, and knew of a hospice agency, AccentCare, who would likely be able to help, and gave me a phone number. I called them, and talked to Mayra Garcia who handles admissions, and they arranged for an assessment the next day.

Two lovely nurses came around to examine her. They looked at her medical charts, and asked about her heart condition, how bad her dementia was, and why she wanted to go through MAID. The nurses had to call the medical doctor at the agency to verify Mom’s eligibility. They said, “Yes, we can work with your heart condition to meet your eligibility criteria. When would you like to enrol in hospice? We can enrol you tomorrow, and have everything done within a week. Mom and I looked at each other. “Um, wait …” I said, “She’s not quite ready yet. We’re just investigating things right now to see what’s possible. Mom might be ready in three to six months, or even later … we’ll get in touch when we’re ready.” The nurses left. But Mom took comfort from the fact that when the time came, she would have an exit strategy.

By this stage, I was having biweekly zoom calls with my two older sisters. Both were disturbed by the idea of MAID. They didn’t take this lightly.

My elder sister Debi lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, and I live in New Zealand. But my middle sister Ruth lives in Los Angeles, and bless her, took responsibility for doing the day-to-day work and oversight that only someone who lived locally could do. As our parents became more frail, Ruth took on ever increasing responsibility for making sure they were OK. She reminded them of upcoming engagements. She took them to medical appointments whenever they needed it, and ensured that prescriptions were filled and recommendations implemented, as they could not be relied on to do this themselves. When there was a wildfire near Mom and Dad’s house, Ruth took our them back to her place to stay until the danger passed. Ruth also took charge of looking after their house which, in an ironic reflection of our parents’ health, was steadily falling into greater disrepair, and she organised contractors whenever anything needed to get fixed.

Initially, Ruth felt assisted death was morally wrong, but she eventually became comfortable with the concept as she witnessed the erosion of Mom’s capabilities and personality. This was difficult for both of them. Even though Mom knew she was becoming incapable of looking after herself, she was grumpy about losing her agency, and did not always take kindly to the help that she needed and had been offered with love.

Debi did the best job of any of us keeping in touch with Mom and supporting her. She called her every single day without fail. They were very close. Debi said, “This is basically suicide and I don’t want to have anything to do with it. She’s asking us to help her kill herself. I have a friend who has cancer who would give anything to live an additional week. She’s throwing her own life away so cheaply. If you want to help her do this, I can live with that, but don’t expect me to get involved or support you.”

I felt conflicted. Nobody wants to lose their parents. And yet, everyone should have the right to choose what happens to them. If a close friend or relative wanted to kill themselves when they were 15, or 30, or 60, or even 70 I’d go to great lengths to work with them to try to get them to see that suicide wasn’t the only solution. But Mom was 97, she’d led a full life, helped thousands of people along the way, but now found everything exhausting, increasingly confusing, and her dementia meant that things were going to get worse, and there was next to no chance they were going to get better. I also felt that in her situation, I would probably want the same thing. She needed someone to help her, and I was uniquely placed to do that.

Despite these differences between the approaches of the siblings, my sisters and I continued to work really effectively as a team, and still continue to do so.

I called Mom as often as I could, generally a few times a week. Most conversations turned back to the same subject.

“I feel the time is coming to check out,” she’d say, “I don’t want to let things drag on to the point where I’m no longer capable of making a choice.”

I’d respond, “You’re still a long way off from that, Mom – your memory test scores show that you’re only a bit less than normal. That’s not bad for someone in their mid 90s. No one could say that you’re anywhere close to not being of sound mind.” But she persisted. She’d have the same conversation with my sisters, which they both found upsetting.

Eventually, in one of our calls, I said, “Mom, look. We all know what your plans are, and my sisters and I find it hard that you bring this up in nearly every conversation. We know you’re serious about this. But please, don’t bring it up again until you have a specific date in mind. And when you do mention a date, I’m going to do my best to talk you out of it.” That didn’t stop her, but every time she’d start talking about “checking out”, I’d ask her, “do you have a date in mind?” I also asked that when she was ready to do this, to please give me two months notice so that I could tie up my affairs in my own life in New Zealand, and come out to LA and help her execute her plans.

And Mom’s MoCA scores continued to decrease.

Mom’s neuropsychologist suggested that getting Mom involved in a project that used her brain would be helpful. Just over a decade prior, Mom had worked on a poetry translation project, Poetry in Hell, a collection of poems from the Warsaw Ghetto’s Ringelblum Archives. But much more recently, she discovered on her bookshelf a book of Yiddish poetry published in 1951 that her father had given her, The Song Remains, or Dos Lid iz Geblibn. Very few of the poems had ever been published either in Yiddish or in translation. Mom decided that this was going to be her next project, to publish these poems from poets who were murdered in the Nazi occupation of Poland, both in the original Yiddish and with her English translations. This would be a major project for anyone, but for Mom, 94, and with dementia, it was a huge mountain to climb.

So she started on page 1 of the book and translated the entire collection of over 160 poems over the next 18 months. She would wake up early every morning, go to the dining room table, and begin her work for the day. Using a computer had become too confusing, so one of Mom’s caregivers did data entry for her. We are still publishing these poems on The Song Remains web site, and will be doing so into 2027.

While she was working on the poetry translation project, her MoCA scores shot back up to normal. This seemed miraculous.

After a very long battle with back pain, heart problems, diabetes, and minor dementia, Dad passed away in late August 2023. They had been married for 76 years, literally a lifetime. Mom missed him terribly.

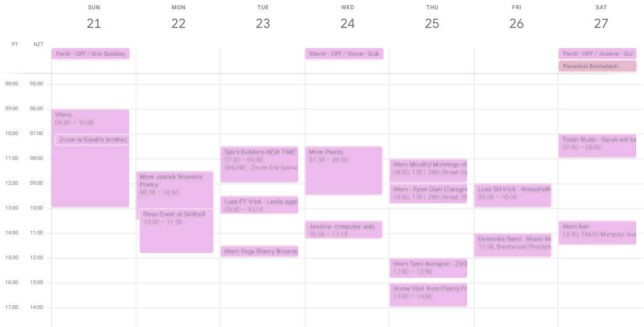

Mom was super busy, with lots of appointments every week, including yoga, poetry classes, medical appointments, dementia band, visits with children and grandchildren, Ryan Glatt… my sisters and I had to implement a shared google calendar just to keep track of things.

But despite being so busy, and so engaged, she knew her mind was continuing to deteriorate, and it was only a matter of time. And without Dad, the evenings were particularly lonely. She had outlived nearly all of her friends. And many of her weekly appointments involved health professionals or structured group interactions. One of her favourite activities was to take a trip to Costco with her caregiver, buy a bunch of stuff that she didn’t really need, and have lunch at a deli on the way home. For her, this was engaging with the world, and her chance to exercise agency.

Her hearing and eyesight were starting to deteriorate more rapidly too. When combined with her memory loss, she found it nearly impossible to read and follow a novel, or keep track of characters in a TV show. Always interested in politics, she watched a lot of cable news, which couldn’t have been good for her mental state.

And still every second or third time we’d talk, Mom would bring up her desire to “check out”. And I’d ask “Do you have a date in mind?” and she’d say no, but it’s not far off.

We began to finish up The Song Remains project in May 2024. The translations are mostly complete, but Mom found it more and more difficult to work, as her dementia began to accelerate again. We had a fabulous launch event, which included academics, Yiddishists, and even the Polish Ambassador to New Zealand. But Mom knew that this was going to be her last big project. She was getting very forgetful, and would mention the same thing four or five times in one conversation. She’d frequently lose the thread of what was being discussed. She’d make appointments with people, forget to write them down or tell anyone about them, and then get confused as to when she was supposed to be doing things. She found this supremely frustrating. And she found the effect on those around her even more frustrating. She did not want to let the people around her down, or even worse, cause them extra effort.

About a week after the project launch, as Mom and I had our regular morning phone call, she brought up “checking out”. “Do you have a date in mind, Mom?” I asked as per usual. “Uh, when are you coming out next?” she responded.

Things had changed. Now she was not only serious, she was ready to act.

I replied, “Well, we’re planning on coming out late June, and we already have some hiking plans. Would you like things to happen after that, say mid July?”

“Yes, that would be good, let’s plan on that.”

“Are you absolutely certain you want to do this? Are things really that bad? You seem pretty ‘with it’ to me.”

“Yes, I’m sure. I’m not going to change my mind.”

I told my sisters. But there was a wrinkle in the plan. My niece Melody, the photographer, wanted to get married, and have the ceremony in Mom’s backyard at the end of July. Melody didn’t know about Mom’s plans, and we didn’t want to ruin her wedding with talk of Mom’s death. So I talked to Mom, and we agreed to postpone her exit until late August, and not make any further plans until after Melody’s wedding. My wife Kate and I went to visit Mom in July as planned. Melody had a wonderful wedding at the end of July, which was well attended by the family. And I made plans to travel back to LA on Mom’s birthday in mid-August to help finalise and execute her plans.

My sisters were still uncomfortable with this. Debi still didn’t want to have anything to do with the plan. Ruth had come to terms with things and decided that on balance, it was better to go along with what Mom wanted to do, but her ongoing discomfort was obvious. She planned an overseas trip to visit her daughter, and would return before the end of August for Mom’s death.

In one of our calls, I asked Mom who she wanted to know about her plans. “I don’t want anyone to know, they can just find out when I’m gone the same way anyone else finds out when someone dies.”

They can just find out when I’m gone the same way anyone else finds out when someone dies.

“What about your brother?”

“I’ll call him.”

“What about your grandchildren?”

“You and your sisters can tell them, but please make sure they don’t tell anyone else.”

“Your medical professionals?”

“Yes, you can tell them on a need to know basis.”

“How about your friends?” “No, don’t tell them.”

“And your neighbours?”

“I don’t want them to know either.”

“Really?”

“Really.”

“Your poetry group, and the other groups you’re involved in?”

“Definitely not.”

Of course Mom later forgot that she had made these decisions, and told a few people. I was surprised that word hadn’t spread further.

A few days later in early August, I got a text message from one of Debi’s kids, in a chat group with his siblings.

“Hi Dave, we just found out today about Bobe’s [Grandma’s] wishes. I wanted to start this thread because my mom is not feeling up for being part of any arrangements for Bobe. This thread has [my siblings and their partners] on it, so we can stay up to date but leave my mom out, at least for now. Please keep us posted on your plans and let us know what we can do.”

I didn’t really want to have this conversation in a group text chat, so I set up a Zoom call for Mom’s grandkids to let them know what was going on. It was a shock to them that she wanted to end her own life, but they understood that it was something that she had been thinking about for years, and was not a decision taken lightly.

We ultimately planned Mom’s death-day for 1 September. Due to Mom’s forgetfulness, I had to remind her of the date several times, and pleaded with her that due to the logistics of people wanting to be there at the end from all over the world, that if she was going to change her mind, to not change the date by a few days, but either permanently, or into the next year. 1 September tied in nicely with Dad’s yartzeit – the anniversary of his death – which was on 30 August. The whole family could be there for both occasions.

I called AccentCare, the hospice that would help Mom fulfil her final wishes. I talked to Walik Edwards, the social worker who manages most of AccentCare’s MAID clients. I asked Walik to explain the process to me. It works something like this:

- The patient is “admitted” to hospice for a terminal condition by a hospice nurse. For many patients, all of the hospice care can take place in the patient’s home.

- The hospice nurse notifies the hospice doctor that the patient is interested in MAID.

- The patient must then have three interviews which include two different doctors to validate their eligibility, confirm that the patient is certain that they want to go through this process, and verify that the patient is not being coerced. This takes place over a period of at least three days. The main criteria, as above, are: Terminal condition with less than six months to live; Able to take the drugs themselves; and Of sound mind.

- Once the assessment is complete and the patient’s eligibility is confirmed, the hospice doctor prescribes the medications from a special pharmacy, to be delivered by courier, which must be signed for. They’re not cheap: Mom’s meds cost over USD 800, and they are not covered by any insurance.

- There are two sets of drugs. The first set are anti-nausea agents. The second set is a cocktail of barbiturates and opiates. These can be left for the patient to take on their own in their own time, but the hospice encourages patients to have a social worker and a nurse present. They make a point of asking you to ensure that the drugs are secured until they are going to be used, especially from children, other people, and animals.

- The patient should fast for 8-12 hours before taking the drugs. Water is fine, but not food. This will prevent nausea and increase the efficacy of the drugs.

- The anti-nausea drugs should be taken approximately one hour prior to the cocktail. The anti-nausea drugs come in pill form, and can be taken with water.

- The cocktail mixture comes as a powder and should be mixed well with 3 oz (85ml) of apple juice immediately before consumption. It reportedly tastes quite unpleasant and burns its way down the throat. The entire drink should be consumed within 90 seconds of starting.

- They recommend that you have some sorbet available to soothe the throat immediately after drinking the cocktail.

- After consuming the cocktail, the patient will become sleepy and close their eyes, and generally fall asleep within a few minutes.

- Their body will slow down and cease functioning. Every patient is different, and this can be a quick or slow process, but many patients die within 30-45 minutes of ingesting the cocktail.

- A nurse will come and pronounce the patient’s time of death. A mortuary will then be contacted to collect the body.

The entire process from first contact to death usually takes one to two weeks, but this can be shortened to three days if necessary.

Walik said that he had helped over 50 people through this process. I asked him if anything ever went wrong, or if there were any other issues. He reported that there had never been a serious issue, and after ironing out a few initial hiccups, in the last couple of years things had all gone very smoothly.

About a week before I left for LA, I made an appointment for Mom to be admitted to home hospice care on the day after I was to arrive and informed Dr Goldstein that Mom was going into hospice and she would be receiving a request for Mom’s charts.

That week, I also talked to my friend Tamara who is a Death Doula. She said, “I’ve never been involved in an assisted death, but everyone I know who has, said that it’s been beautiful.” Her key advice to me was to think about the people around Mom, and what would make the experience most meaningful for them.

I also talked to Mom’s rabbi, who was very helpful and was keen to be there when Mom died. She had never done this before, but had some ideas around reconstructing Jewish ritual for someone going through MAID.

In one of our phone calls, I asked Mom who she wanted to be there at the very end. “I don’t want a big party,” she said, “Only my children, and their partners – if they want to be there. I don’t want to force any of you to be there if you don’t want to be. And Rabbi Amy.” That number sounded about right to me. Nobody wanted to turn this into a spectator event.

The morning arrived for Mom’s admission appointment, and a nurse from the hospice came to visit at Mom’s house. We all sat down together to talk at the dining room table. The nurse took Mom’s blood pressure, pulled out a couple of notebooks, and started asking Mom some basic questions about her health, her history, and her life in general. After a few minutes, the nurse said, “I’m sorry we can’t admit you, as you’re clearly not eligible.” I replied, “What do you mean? She was eligible two years ago, what’s changed?” The nurse said, “You’ve been referred for entry to hospice with a primary diagnosis of dementia. The rules for entry to hospice with dementia are very strict – you need to only be capable of saying a couple of words, and Sarah’s dementia is clearly nowhere near as advanced as that.”

Mom and I looked at each other. Mom nearly yelled at the nurse, saying “I want to end my life. I thought you could help me do that.”

“Hold on,” I said, “two years ago, Mom had a primary diagnosis of heart disease. Have you seen that in her charts?”

“I haven’t seen her charts,” the nurse said. “But she definitely does not qualify for a diagnosis of dementia.” The nurse left, and Mom was close to tears.

I called the Hospice, and talked to Mayra, my main contact I’d been working with for two years. I asked, “How come the nurse didn’t have access to Mom’s charts? Two years ago, her primary diagnosis was heart disease, and it hasn’t gone away, if anything it’s gotten worse.” The nurse said she’d have to talk to the hospice’s medical doctor and get back to me. And so we waited.

We waited by the phone all day. No response. At 4:30, I called Mayra again but she had gone home for the day. The receptionist said that we should try again in the morning. Next morning, I called Mayra again, and she said that she had contacted the hospice’s head doctor, but she was very busy, and she hoped that she would be able to get back to me by the end of the day.

I guess I could just walk into the ocean.

Mom was very worried. “What if we can’t do this?” she asked. “I guess I could just walk into the ocean.” I had thought of this, but someone would have to drive her there, and she’d need assistance getting to the water, as she used canes or a walker. In my mind, I pictured the police interview afterwards and it wouldn’t look good.

She asked, “Are there any other options?”

Having done some research into this, I said, “You could end your life through voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED). You’d need to have tremendous willpower, and it could take several weeks. It would not be at all fun.”

“I think I’m prepared to do that,” she said.

“Evidently you can buy cocktail ingredients in Mexico over the counter for euthanising pets. I suppose I could go there and try that, but it would be a bit risky for me coming back across the US border with illegal drugs, especially given that I’m not a US citizen.”

“I wouldn’t want you to take that risk,” she said.

“I understand that assisted dying is legal in Switzerland, and they’re one of the only countries in the world that takes foreigners. I guess we might be able to figure out a way to get you to Switzerland,” I mused. The thought of embarking on international travel with Mom and taking her through LAX and beyond, given her health condition, mental state, and lack of mobility seemed several bridges too far for me. How would insurance work? What would happen if she got sick or injured along the way? Would we only buy her a one-way ticket? Would we end up with her ending her life in a lonely hotel room in the back streets of Zurich?

“I’d like you to take me to Switzerland if we can’t work with the hospice,” she said.

“Mom, you don’t have a passport. You don’t even have a valid drivers licence. I suppose it would be possible given enough time, but it could take months. Let’s not catastrophise, let’s wait until we hear back from the hospice.”

“OK,” she responded, but I got the feeling she was still terrified deep down inside.

We didn’t hear back from the hospice that afternoon. We were both pretty miserable.

Next morning though, I got a call from a different hospice nurse. She said she had Mom’s charts, and could come over that morning and assess Mom. This time, Mom was in bed for the interview. The nurse arrived and was almost too cheerful. “How are you Sarah?” she asked in a singsongy voice, and Mom talked about how she wanted to end things. “I see from your charts that you have a heart condition. How does this affect your day-to-day life?” “I can’t walk very far at all now,” Mom replied. “I see you have a prescription for nitroglycerine, have you used that recently?” Mom said yes, she’d taken it a few times in the last few weeks. This was news to me, but I didn’t interrupt. “I can see some minor swelling in your legs,” the nurse said, “and you seem to be a bit short of breath. I think we can admit you for atherosclerotic heart disease. Let me make a phone call to our medical doctor, as she’ll have to sign it off.” The phone call was made, and fifteen minutes later Mom was filling out admission forms, and was admitted to hospice care later that day.

All sorts of equipment started arriving at the house. Oxygen. A hospital bed. A portable toilet frame. A “comfort pack” containing morphine and lorazepam. None of this stuff ever got used.

That afternoon we went to her regular appointment with her neuropsychologist and her nurse. Mom told them of her plans. They were very upset. “Why do you want to do this, Dr Moskovitz, you’re doing so well,” they said. “I feel the time has come for me to check out, and you’re not going to change my mind.” They gave her their usual MoCA test which she was doing really well on, but just near the end of the test, Mom said, “I don’t really see the point in continuing this. I want to go.” It was very awkward saying goodbye to these professionals with whom we had been working for several years. “I guess we won’t need a next appointment,” I said. We said our goodbyes, which were clearly strained, and left. Nothing prepares you for this kind of event.

We’re used to death arriving unexpectedly, and even when it’s expected, the timing is almost always a bit random. It was just weird basically saying, “She won’t be able to come next Thursday because she’ll be dead.”

It was just weird basically saying, “She won’t be able to come next Thursday because she’ll be dead.”

In my mind I had started framing Mom’s plans as her going away on a very long trip, from which she wasn’t going to return. She’d be going to a place where she no longer had to worry about the future, or grieve at the daily deterioration of her own body, abilities, and personality.

Life at Mom’s house in hospice care continued on much as it had been. She didn’t use the hospital bed or any of the other equipment, still had her 24×7 carers looking after her, and kept up most of her appointments. Mom and I also did more fun activities than usual – she had a bit of an energy surge as she knew the end was approaching. We went for walks along the bluffs and the beach, went out to restaurants that she’d never been to – or in some cases, had been to several times but had forgotten due to her dementia. We met up with the grandkids that were in town. She had more visits than usual with her friends. We tried hard to make her last days as good as they could possibly be.

I started planning out Dad’s yartzeit for Friday 30 August, and invited all of the immediate family to come for that. Unspoken, but very clear, was that Mom was planning to die a couple of days later. There were grandchildren literally all over the world – Australia, New Zealand, Israel, New York, Northern California and of course LA. It was going to be a major logistical exercise. Thankfully, two of my nieces took charge in organising catering, equipment rental, and the like.

We hadn’t yet completed the hospice requirements though. She needed to have her three interviews involving two different doctors, and there was still some risk that she could be disqualified for some reason. Understandably, the hospice doesn’t want to rush these things. The doctor interviews were scheduled to take place on Zoom on the following Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday before her planned departure on Sunday. I helped Mom prepare for these as one would help one of their friends prepare for a school exam. We knew they were going to ask her questions about her medical condition, so we rehearsed her answers about her deteriorating heart condition. We knew that they wanted to be certain that she was “of sound mind”, so we practised questions about the day of the week and other MoCA-like items.

Mom went through the interviews. It was nerve-wracking – she didn’t want to blow it. By the time we had got that far into the process, I think the doctors were on Mom’s side. They asked her if she was certain she wanted to do this, and she said that she was. Rather than give her a MoCA like test, the first doctor asked Mom about her youth and her career. The Professor Sarah Moskovitz of old came out, and she confidently told them about all of her professional accomplishments succinctly and articulately – there was no chance of any doubt that she was of sound mind. They asked about how her heart condition was affecting her life, and she told them. They asked her when she was planning to go, and she said (after looking down at her cheat sheet we had prepared) on Sunday September 1st. They seemed a little surprised but impressed that she was so determined, and that having made the decision, she wanted to do things relatively quickly.

The only slight curveball was when the second doctor asked Mom if she had any trouble swallowing. “As a matter of fact I have, only recently” she said, trying to please them. I was puzzled – she hadn’t mentioned this to me. “The reason I ask,” the doctor said, “was that you need to be capable of swallowing the drugs, which are uncomfortable to swallow. Do you think you could do that?” “Yes, I’m sure I can do that” said Mom. I breathed an inaudible sigh of relief.

After the second interview, the two doctors conferred to determine the patient’s eligibility. She had passed, and everything was set to go according to plan.

The third interview didn’t involve many questions other than was Mom sure that she wanted to do this, and then went into a description of how the procedure works, as had been described by Walik above. I took detailed notes, not wanting to get any of it wrong.

The drugs were ordered, and scheduled to arrive the next day. I went down to the supermarket and had a look at the sorbets so that Mom could decide what she wanted her last food to be. She chose mango.

I had contacted all of Mom’s grandchildren, who were all arriving in LA at different times, and put together a roster so that each one could spend an hour with her to say goodbye.

I had contacted all of Mom’s grandchildren, who were all arriving in LA at different times, and put together a roster so that each one could spend an hour with her to say goodbye. I had been worried that without any structure, some of them would inadvertently take more than their fair share of time, and that some would miss out. I was careful to schedule plenty of break time between sessions so that Mom could get some rest in between, as well as having some unstructured time.

On her final Wednesday, I took Mom to her regular appointment with Ryan, the cognitive physiotherapist. This wasn’t going to be a normal session though, this was Mom’s exit interview. Mom had been Ryan’s star patient – one of his oldest, yet one of his most successful. He asked her a number of procedural questions, but then asked her: “Sarah, to what do you attribute your impressive ability to stave off the effects of dementia for so long?”

Mom thought about this for a bit. She said, “Well, there are three things. First, I’m physically active. I try to go for a walk every day, I do yoga regularly, and I come to your cognitive physio sessions every week. Secondly, I have connections with a lot of different social groups. I have two poetry classes, Torah study every week, my family, the Spirit Builders group, Mindful Mornings every Wednesday, and see my neighbours too. Third, I’ve been doing important and meaningful work on poetry translation that I know I’m uniquely placed to do – this is an important part of my legacy, not only for the poetry, but also for preserving the memory of the poets and the Yiddish language which they loved.”

I was stunned. Mom couldn’t have told you what she had said five minutes ago, what she’d had for breakfast, or who came to visit earlier in the day. But she’d managed to articulate the key components of her fight against dementia, as Professor Sarah Traister Moskovitz might have explained it in a lecture.

On the Friday night 30 August, we had Dad’s yartzeit – he had died exactly a year prior. We lit a memorial candle for him, before lighting the shabbat candles. We had a ma’ariv (evening) service in Mom’s backyard and said kaddish for him, the prayer recited when remembering our loved ones who have passed away. Almost all of the family had been able to come. After the service, we sat around in a circle telling stories about Dad. We made a point of focusing this event on Dad, as I’d felt that he’d been somewhat eclipsed by all of the attention Mom was absorbing. And it was beautiful. Mom and Dad had lived a wonderful life together, and Mom said that she was happy she was going to be joining him soon.

After the yartzeit. I said to Mom, “Tomorrow night will be your last night. Your whole family will be here. Is there any particular way you’d like to spend it?” She thought for a brief moment, and said “I’d like to have a family sing-along,” and so we made plans for a sing-along the following evening.

The next morning, I asked Mom, “How are you feeling?” She replied, “I’m feeling good. I’m feeling ready. It’s really nice having everyone here and getting time to spend with them. Thank you so much for organising everything, David – I couldn’t have done this without you.”

My wife Kate asked Mom about her thoughts on what happens after you die. Without hesitation, she answered, “Well, I don’t know what happens after you die, but whatever it is, I can’t see how it can be worse than living here without my mind. And you know, sometimes I feel them round me – my mother, my husband. So whatever it is, I’m not scared.”

The drugs arrived that morning, and I made sure to get Mom to sign for them. I wasn’t going to do it, and nobody else was. The bottles containing the drugs looked pretty much like any other prescription. When the drugs arrived, I put them in a bag, taped them shut, and stashed it at the very back of the fridge. I went to the supermarket to get a small bottle of apple juice and a container of mango sorbet.

Mom continued to meet with her grandchildren according to the roster throughout the day, and we had the sing-along in the evening. Debi and her son played guitars, and my eldest son was on the fiddle. We sang for at least a couple of hours, covering old family favourites, standard folk tunes, old Yiddish tunes, some Irish standards for good measure, as well as some call-and-response sea shanties that everyone could join in on. People said their final goodbyes to Mom on their way out, which were tearful but graceful.

The next morning was Mom’s last day, and we decided on 10am as the time Mom would take the cocktail. All the grandchildren had said their goodbyes over the previous days, and the last day was really for Mom and her children. My wife Kate and I arrived early, having arranged for her final 24×7 caregiver shift to end at 8:30am that morning. Kate asked Mom how she was feeling. “I’m feeling good. I feel that my life is complete.” I said, “complete as in you’ve dotted all the i’s and crossed all the t’s?” She quipped, “I’ve always been good at spelling. I’m going to end things with an exclamation point!” Kate couldn’t resist adding, “As you head toward the big question mark?”

I asked her if she had any last instructions for me. She gave me a list of people she’d like to leave small presents for, like Ryan, her yoga teacher, her caregivers, her hairdresser, and her cleaner. I told her I’d make this happen. She said, “I want you to write about this experience. There isn’t a lot of information about assisted death available, and I want people to know more about it.” I promised to do this. And finally, “I want you to get a Harris / Walz campaign sign and put it on my front lawn.” I laughed. Mom was political right to the very end.

My sisters arrived shortly after this, and we sat around chatting. I again asked Mom if she was sure she wanted to go through with this, and she said yes. I reminded Mom that when presented with the cocktail, she should drink it within 90 seconds, in one go if possible, and that it wasn’t going to taste nice. If she were going to change her mind, the time for that was now. She didn’t want to put herself in the situation where she changed her mind halfway through the cocktail. I then went into the kitchen to make sure the drugs, apple juice, and sorbet were ready. At 9am, I gave her the anti-nausea drugs with some water. Shortly after that, Rabbi Amy arrived, and joined the conversation, followed by Walik with a nurse from the hospice. Mom gave a short final speech.

As 10:00 approached, Rabbi Amy got Mom to recite the Shema, the affirmation of God’s unity that every Jew is meant to recite on their deathbed. Mom sang it, of course.

Rabbi Amy then read a few poems by Debbie Perlman’s collection New Psalms for Healing and Praise.

For healing

Surround me with stillness,

Tiny ripples spreading across the pond,

Touched by one finger of Your hand,

Calmed by the warmth of Your palm.

Croon the wordless melody

That fills my being with peace.

Under the spreading tree of Your affection,

I will sit and meditate

On the goodnesses You have brought,

Counting the happy moments like glistening beads

Strung to adorn my days.

Light the shadowed corners with gentle glow,

To fill my being with peace.

Drape about me the dappled sunlight of Your teachings,

Opening my eyes to the search,

Clearing my heart of small distractions

That I might find the answers within myself.

Blow the breeze of compassion upon my brow,

Breathing the sigh of peace.

Let me rest by the water,

Probing gently for the sense of what I see,

Releasing my hurts to restore my spirit,

Feeling You guide me toward a distant shore.

Last Days

Guide me, Holy One, on this final journey,

Your hand pointing the way,

Your loving eye upon my face

As I seek my new dwelling.

Surround me with Your kindness,

Embrace me with tranquility;

Soothe my fears with the surety of Your care,

Even as I release my tears to Your custody.

Then shall I find Your eternal gift of peace,

Laid out for my notice and my strength.

Linger near, Holy One, through these trials,

Easing my way as I fly to Your keeping.

For Courage

You fly, O Eternal,

Between the heavens and the earth,

Multi-colored plumage

Leaving paths of brilliance

To lead my soul to You.

Circle back, O Flyer;

As I turn to follow Your path,

Draw me across the sky.

Your wings flutter,

Hovering here, above my head,

Stalling to wait until I look up,

Lingering to catch my heart,

And lead my soul to You.

Beckon me with Your throaty call

As I spread the wings of my hope,

And lift, singing back Your notes.

Slow for me, hold back Your speed,

For my wings must gather courage

As I strive to follow the spiral Of Your passage

That leads my soul to You.

Guide me on, O Flyer,

Diving through clouds into sunlight,

To rise ever higher.

The time had come for Mom to end things. I hadn’t realised that we should have organised someone to mix the cocktail powder and apple juice, so I went ahead and did this, stirring vigorously. I walked over to the bed, and said, “Mom, are you absolutely certain that you want to do this?” “Yes,” she said, and she took the drink with both hands, and drank it down in one go. I quickly gave her a tablespoon full of the mango sorbet. She wanted more, and I gave her another. She laid back against the pillows in her bed. My sisters and I were holding her hands.

We sang some songs: Ozi V’zimrat Ya (God is my joy and my music), Olam Chesed Yibaneh (I will build this world with love), Oyfn Pripitchek (By the stove).

Mom’s last words were, “It’s OK, I feel a warm wave coming over me.”

It’s OK, I feel a warm wave coming over me

Debi couldn’t bear to be there when Mom actually died, so she went outside and sat on the couch on the porch directly outside Mom’s bedroom window.

After a few minutes, Mom seemed to be peacefully asleep.

We played some music that Mom had requested earlier: the first movement of Bach’s concerto in D minor for two violins and orchestra, and then the second movement of Beethoven’s violin concerto in D major.

US Marine Chamber Orchestra, public domain

By the time the second movement had finished, if Mom was still breathing, it wasn’t visually perceptible.

Debi said that about this time there was a sudden gust of wind in the backyard, and a group of birds and butterflies landed on the avocado tree directly in front of her. She said it was a bit Disney, but she’s convinced that’s when Mom actually passed.

Another nurse arrived some time after that, and pronounced Mom’s death at 11am. The cause of death on the certificate is atherosclerotic heart disease.

The day following the funeral, I planted a Harris / Walz campaign sign on her front lawn.

Looking back, I find it hard to imagine a better way to go. Mom had been able to plan things on her own terms. She had lived a long and very full life, positively touching the lives of many people. She avoided turning into something she did not want to become. She did not seem to experience any pain or discomfort. She was happy. She felt her life was complete. Her final days had been special, in deep conversations with her grandchildren. She lost consciousness with her children holding her hands, listening to beautiful music, having spiritually prepared for the next stage.

It was one of the most beautiful things I have ever experienced.

This was in stark contrast to Dad’s death, which had taken place in a sterile hospital ward after a long, rough, and painful journey.

I miss Mom, and haven’t really fully adjusted to her absence. Sometimes I wake up in the morning and think, oh I’d better call Mom now. She’s with me in my DNA and in my behaviour patterns. She was a role model for so many different aspects of my life and I can trace a line from many of my personality traits directly through her. So even though she’s gone, she’s still with me, and always will be. I’ll always love her, and I’m happy and fulfilled to have been able to help her carry out her final wish to die with dignity.

* not their real name

Dave, that’s a great piece of writing, and a really good insight into assisted dying. Thank you for sharing this.

Sending you much love

Sue

I cried while reading this – it is so moving and such a tribute to your mum, Dave, and to all the family. I cannot imagine a better experience of dying.

Dave, you’ve given a gift to so many families by sharing your experience. It’s a blessing to help people understand the MAID process and your mom’s decision to participate.

Sending peace and love to you and your family. XO

Dave, this is so beautifully and compassionately expressed. Thank you for sharing this.

Dave

What a touching and very useful experience you’ve shared.

We all live different lives and and yours and your families are unique.

But sharing this has provided us, at least, a platform for discussion.

We are probably more preoccupied with death than most and have been since last century. But you’ve presented a scary situation with clarity and love and compassion. And a bit of drama that you could have done without. But it was resolved pretty quickly.

Thank you. Your parents have clearly been a blessing for you and for your family. How wonderful that your children got to know them – and their cousins.

Don & Julie

Dear David, Debbie, and Ruthie,

Your mother‘s life was a blessing in my life and for so many others. She taught me so much about caring and doing what needs to be done all the way through with joy and passion. I met her fairly recently and felt so close to her so quickly as we drove every Friday morning to Torah study. Your sharing the final part of her life was beautiful and fitting for the elegant, intelligent, loving woman she was. Her spirit is part of mine now. I treasure the friendship and the time she allowed me to share with her.

With great admiration for your family and for Sarah,

Judith Ubick

What a moving account Dave. Thanks for sharing this story of your amazing mother. Your support and that of your sisters must have meant so much to her. I found this quite profound. Thinking of you as you process the thoughts and feelings at the ending of your mother’s journey. Sue

Hi Dave,

As you know, I know. I have been through my parents version of this story.

A wave of sadness come over me as I read your words. I hope that you and your family are OK as we come to the beginning of another calendar year. The grief does mitigate but the memories and the DNA, as you say, lives on. Take care down there.

Thank you for sharing this. I knew Sarah for decades and have such wonderful memories of and with her, especially when we interviewed one another about translating poetry for a Jewish literary journal, Sarah from Yiddish, of course, and I from Russian.

My husband died of Alzheimer’s in Feb. Dementia and Alzheimer’s are devastating diseases.

Dave, thank you for sharing your mother’s journey, I’ve learned so much reading your article. What a wonderful son you are, I cannot imagine any of this being easy but a blessing that Sarah could transcend on her own terms. Sending love.

Hi David,

I don’t know what to say or where to start. All I can come up with is that Sarah always struck me as a dignified and insightful person, with strength of character by the truckload. So, deciding to go out this way is understandable and appropriate. She was strong enough to make this choice and you guys were equally strong in helping her, even in many practical ways, to say nothing of dealing with the philosophical issues. Your Dad used to say that “Old Age ain’t for Sissies” – well, your mother proves there is plenty of courage in old age as well. Would I be able to do what she did ? I might have the strength, but maybe not. But anyway, her going out in this way proves she was special to the end.

This is one of the most beautiful things I have read in a long time. I had to read it twice, two days apart from each reading, because your words deeply impacted me. Thank you for sharing it with us.

What an amazing read. Thanks so much sharing this beautiful and detailed story.

Dave thank you for this.

Your own strength shines through too. This is beautiful, and beautiful writing. I’m crying, but not so sad.

Clare

My condolences to you and your family, and all who loved Sara.

Karen Bewick

Thank you, Dave.

I’m glad you wrote this story. It is relatable in so many ways to me. Your story also broadens my horizons and deepens my understanding of being human.

Dave – thank you so much for sharing this – beautiful and inspiring. And also a critically important guide for so many of us who need to navigate these issues

Dave, thank you so much for sharing your family’s experience. I’m a hospice nurse considering working with a MAID affiliated organization. I have now made up my mind. Peace and comfort to your family.

This is extraordinarily beautiful, thoughtful and hopeful. Who she is and who you all are shines through. This will help and inspire many many people. What a legacy you all created together. Arohanui x x

What a beautiful, moving and positive experience ! Dana and I were very fond of, and in awe of Sarah. May her memory be a blessing to the whole family.

Sumner and Dana Fein

Aroha tino ki a koe me tou whanau. Beautiful story of your mama and papa.

Thank you Dave & Sarah (through Dave, as she requested) for sharing such a personal, beautiful & important part of your lives.

Thank you for writing this Dave, what a beautiful thing to do for Sarah, and a beautiful way to leave. So impressed by her bravery, strength, and conviction. I only met her a few times, but Sarah made an impression on us as kids when we visited, both of your parents did.

Much love to you and the rest of the family,

Ben

Thank you for sharing this experience, Dave. It’s a great piece of writing and I especially liked the humor. For people like me, who are interested in an exit of this nature (at the appropriate time), it’s a very encouraging example. I’m confident “the big question mark” is treating your folks kindly. Much love to you and Kate 🧡

Thank you for sharing this, Dave. It’s deeply moving in its raw beauty and honesty. It’s truly special that someone is willing to write about this. My heartfelt condolences.

Thank you for sharing such a personal and powerful story, Dave. Your parents obviously had remarkable lives and as someone who has lost both parents in recent times, the whole issue of how our lives end is close to my heart. In wanting her end-of-life experience shared, your mother’s legacy is even more lasting and poignant.

What a remarkable gem of sharing– and tribute to Sarah! How typical of her to think of how this writing could inform/help other people. We knew Sarah through Kehillat Israel. Here is a woman who lived an extraordinary life …. and CHOSE a beautiful death. Courage, strength, faith, high intelligence … she embodied all of these qualities. She spoke softly and carried a big soul, a flip of the FDR adage. It is heartwarming that Dave kept his word and wrote about this to help others. She was a true Woman of Valor.

A beautiful tribute, thank you for sharing your mother’s story.

You are a wise and kind man, and a loving son. I am filled with love and awe at how you and your sisters, along with your mother (my beloved Aunt) managed to understand one another, and to respect the healers while also really listening to your Mom. A more loving act I have not yet heard. May you all be at peace. Your parents memories ARE a blessing, and may they always be a blessing. With love, Sharon

20 May, 2025

Dave, thank you so much for today’s tribute to your mother Sarah, and to the Yiddish language. This is an amazing piece of writing from the heart–in doing this, you have given such a gift to those of us who knew and loved her. ..just as she asked you to do.

Leah Schweitzeer