I recently participated in a “Procurement Hackathon” event run by the Chris Webb and Jane Kennedy at Department of Internal Affairs in Wellington. Rolled into this event was the launch led by Minister Clare Curran of the DIA Marketplace, which is starting life as a directory of third-party pre-approved services, many of them SaaS, that government agencies can “just buy” without going through a lengthy procurement process. To those of us in the room from the private sector, this hardly seemed revolutionary, but was a bit of a great leap forward and the culmination of many years work for the DIA folk. They have big plans to expand Marketplace to cover a wide range of goods and services, and we should applaud them for their efforts to date and wish them well and support them iterating what is a solid MVP.

You can view a set of collaborative notes from this part of the day, if you’re interested.

The rest of the day, ably led by Mike Riversdale, was spent reviewing the outputs from last year’s “Procurement Hackathon” which included a strange set of coloured cards with aspirational statements on them. Our job on the day was to divide ourselves somewhat randomly into teams, choose a card, and develop a pitch around why this was an important thing to do to encourage better procurement practices in government.

Our team’s chosen task was:

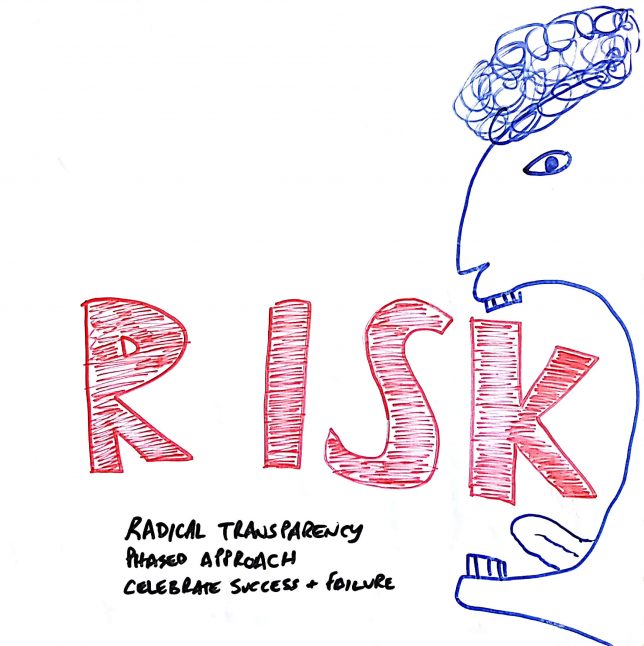

How do we change risk appetite so that organisations understand and mitigate risk rather than avoid it.

The crux of our pitch:

Government is currently very risk averse due to the potential of negative publicity by the public, and opposition, and ultimately being voted out of office. At the same time, taking on no risk means that it’s difficult to make progress – any change implies some risk. Ironically, sometimes it’s riskier to take no risks at all than it is to take small, managed, progressive risks. We believe that we should change government’s risk appetite from not wanting to take any risks, to taking some risks, and take the public, private, and community sectors on the journey with us.

Our main hurdles are the fear of failure and associated stigma – opposition and media ridicule are baked into the structure of our democracy. Failure seems to be a lot more visible than success, and you can witness this in the news cycle. Tall poppyism and the lack of appreciation of the value of innovation are also issues.

What can we do about this? The key is to increase the risk appetite of the public sector. We can do this by celebrating success, celebrating failure, and celebrating the resulting wisdom that comes out of the work that we do. We should appreciate and reward people for trying, and we can do this by rating their overall portfolio performance rather than looking at individual failures or successes. People and organisations that take managed risks will generally perform better over time than those who take no risks at all, or poorly manage their risk profiles.

We need to integrate our learning from failure into our standard business practices, we need to get better at continually monitoring and assessing the risks that we take, spread the risk wherever possible, improve our resilience by engaging in parallel development of a number of different potential solutions to the same problem. We should generally take a phased approach to our projects so that we can make our mistakes and learn as much as possible about the problem space as early as possible.

We need to have honest conversations about the risks that we take rather than sweep them under the carpet.

We’ll know we’re successful when we can measure lower failure rates in large projects, increasing the number and quality of innovative services coming out of government, increasing the level of collaboration between agencies on projects, higher public satisfaction with our services, and higher satisfaction of public servants in their jobs.

We were asked to come up with one crazy idea, and this is it: we should have radical transparency of the information coming out of government projects. Government could ask the opposition to collaborate on setting acceptable risk parameters. You won’t get fired for failing, but you could get fired for hiding information about the factors that led to the failure.

Our ultimate goal is to build a future where we’re all willing to take the risk of failure, but we manage our risks wisely, and learn through the experience. Innovation and taking managed risks become integrated into the performance management of every public servant. The private sector will be so impressed with this approach that they will want to emulate it, and seek advice from government on how they can use this approach in their businesses.

We want New Zealand to be known as the country with the most open, transparent, collaborative, and innovative government in the world.

I’d like to thank our fantastic team that worked together so well on the day:

- Stephanie Ellingham from WSP Opus

- Emma King from ACC

- Mel Gollan from RIP Global

- Marni Gaskell from Spark

And finally, here’s a video of our pitch for your entertainment, part of a larger DIA blog post reviewing the day:

Love this as a concrete proposal for progress: “Government could ask the opposition to collaborate on setting acceptable risk parameters.”